In Everson v. Board of Education of Ewing Township, Justice Hugo Black twisted the phrase “separation of church and state” and unwittingly unleashed the now-accepted belief that Christianity has no business in the public square.

The United States of America prides itself on the freedoms it protects through its Constitution, most notably the freedom of religion.

And yet the last century has been marked with constant battles over religious liberty and what, if any, role Christianity and religion should play in the public square. Whether it’s the Colorado cake artist who spent 12 years in court for refusing to bake a wedding cake for a same-sex wedding or the high school coach who was fired for silently praying after games or the Christian parent banned from adopting children because she refused to agree to take her children to gay pride events, religious liberty has taken center stage in the American culture wars.

The battle has pitched over the line between the secular public square and religious practice, as courts try to strike the balance between neutrality and freedom. It may feel like this is just how things have always been, but that is not the case.

There was once a time when religion — particularly Christianity — was seen as the cornerstone of the United States, an indispensable part of its foundation and culture. That all changed in 1947 with the Supreme Court’s ruling in Everson v. Board of Education of Ewing Township. For the first time in American history, the ruling in Everson used the 14th Amendment to directly attack religious freedom and built the foundation for the hostility towards Christianity that we endure today.

Faith and the Founding

Before diving into Everson, it is important to understand the relationship between faith and the American people at the Founding of the nation and beyond. The First Amendment is both well-known and well-loved by Americans today for protecting several key freedoms, including speech, religion, and assembly.

The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

The wording is pretty cut and dry: Congress cannot establish a national religion in the United States. What many Americans do not realize, however, is that Congress used to be the only body restricted by this clause.

At the time of the Founding, several state governments had established churches within their boundaries, providing public funds to churches and religious organizations and even mandating a profession of faith to hold public office. The practice of establishment lasted into the mid-19th century, with Massachusetts being the last to disestablish its state church in 1833.

Despite the fact that states no longer had their own official religion, many of them still retained blasphemy laws, laws against operating businesses on Sundays, and religious tests for public office. These states often had provisions encouraging religious liberty while simultaneously having legal preferences towards Christianity.

While this may seem strange to modern Americans who have been inundated with the gospel of secularism, this was completely normal to the people living at the time.

This was because the Founding Fathers of America recognized the important role of faith in public society.

In his Farewell Address, President George Washington remarked that “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.” John Adams, in a 1789 letter to the Massachusetts Militia, said that the U.S. Constitution was “made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

The U.S. Supreme Court even declared America to be a “Christian nation” in the oft-forgotten 1892 case Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States due to the history, social customs, and legal tradition of the nation. This understanding began to fade at the turn of the 20th century.

A Sharp Turn in Legal Reasoning

When the 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868, its clear purpose was to protect the rights of the recently freed slaves living in the United States through its Equal Protection Clause.

The early 1900s, however, brought a revolution in legal reasoning. Judges started interpreting laws using the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause to determine if the government was violating someone’s fundamental rights, even if the government entity involved was following proper procedures.

This legal principle, known as substantive due process, would later lead the Supreme Court to “recognize” rights like abortion and same-sex marriage via a “right to privacy” — even though those rights aren’t actually found in the text of the Constitution.

While those effects are well-known today, what is less known is how this shift in legal reasoning reframed the importance of faith in the public square.

The shift was subtle, but it would quickly take hold and never look back.

In 1925, the Supreme Court decision in Gitlow v. New York applied free speech protections to state and local governments for the first time in American history.

While limited in scope, Gitlow set the groundwork for Everson v. Board of Education of Ewing Township, which would introduce the idea that the Establishment Clause didn’t apply to just government, as clearly denoted in the Constitution, but that it could also be applied to individuals who act as the government’s agent. In other words, a public school teacher who prays silently at her desk could be seen as implicitly endorsing a religion to her students, which would be a violation of the Establishment Clause.

In practical terms, the Court moved from plain-text to extra-text and even imaginary-text interpretation, and it ultimately served to flip the First Amendment upside down.

Twisting and Inventing Words

Here’s how Everson played out: Under the authority granted by New Jersey Law, Ewing Township’s Board of Education authorized the reimbursement of money spent for bus transportation for schoolchildren, including the transportation of children to Catholic parochial schools. Orel J. Everson, a local resident, sued the Board, contending that the reimbursement violated the Establishment Clause.

The case eventually made its way up to the Supreme Court, which in a 5-4 decision, ruled against Everson. The majority concluded that since the funds were used indiscriminately for all children, not just for those enrolled in religious schools, the school district had not violated the Constitution.

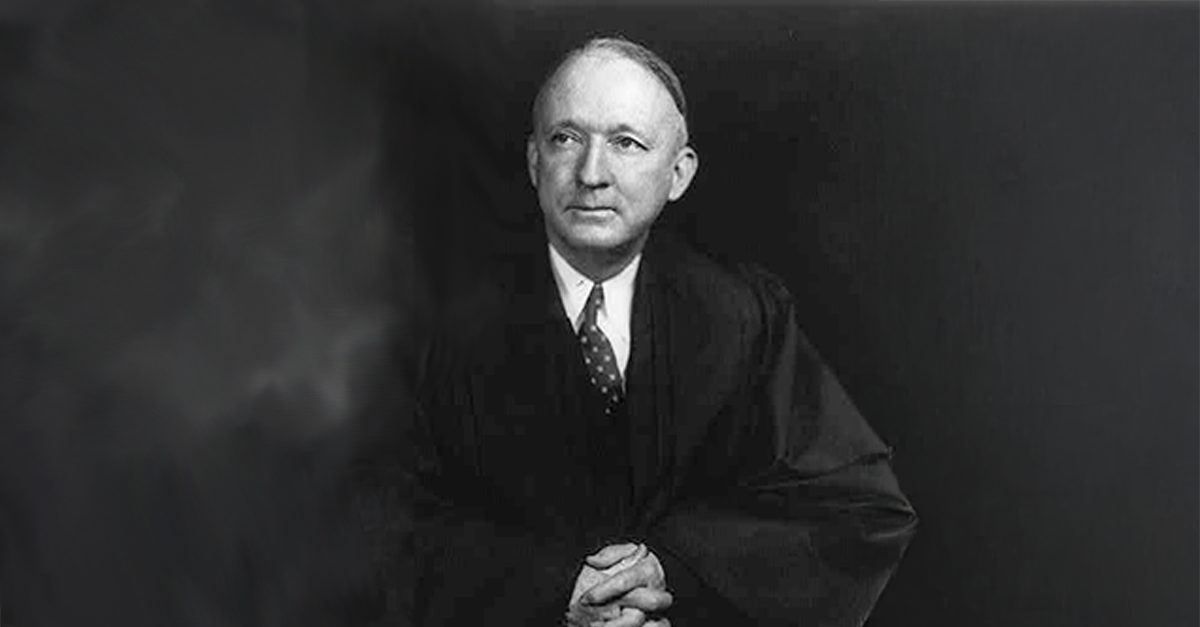

Nonetheless, Justice Hugo Black, who wrote the opinion, used the case as an opportunity to reframe the Court’s view of the Establishment Clause, writing,

“The ‘establishment of religion’ clause of the First Amendment means at least this: Neither a state nor the Federal Government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws that aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another…. No tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions, whatever they may be called, or whatever form they may adopt to teach or practice religion.”

Justice Black’s reasoning in the decision relied not on prior court precedent nor on the nation’s history and tradition but rather on a short 1802 letter written by then-President Thomas Jefferson to the Danbury Baptist Association in Connecticut. Jefferson wasn’t suggesting a new legal standard; he was only trying to assure church leaders that the federal government would not interfere with church operations. He, like the other Founders, believed that while faith — particularly the Christian faith — should play a role in influencing both national and local politics, the state had no business interfering in matters of religious doctrine.

However, Justice Black twisted Jefferson’s words and then added to them, somehow reasoning that “The First Amendment has erected a wall between church and state. That wall must be kept high and impregnable. We could not approve the slightest breach.”

Despite being out of step with the majority of American history, this new logic would become the basis for eroding religious liberty in the United States over the course of the next seven decades.

The new standard of “separation of church and state” would kick in just one year later when the Court ruled in McCollum v. Board of Education that public school classes on Christianity and Judaism are unconstitutional. By the 1960s, the Court was well on its way to finding all manner of public faith expressions to be illegal. It banned prayer and Bible reading in schools in School District of Abington Township v. Schempp and even moments of silence in Wallace v. Jaffree.

In all, over 50 cases from the Supreme Court have since relied on Everson’s framing to expand the areas and scenarios where religious faith was off limits. These decisions, as noted in a prior Standing for Freedom Center article, “served to slowly shift the standard for religious expression from that of ‘neutrality’ to outright hostility.”

Or as author Aaron Renn explains in a recent article for American Reformer, the Everson decision initially shifted the United States from a “positive world” that uplifted Christianity and faith to a “neutral world” where the Christian faith is neither promoted nor demeaned in the culture but is just one of many personal choices an individual can make.

But it didn’t stay there.

As we have seen over the last decade, there is no such thing as “neutrality”; it is effectively a vacuum that will quickly fill itself with something.

And so the United States soon morphed into a “negative world,” where Christian values were no longer respected but seen as “undermining the social good” and where secularism became accepted as the only “neutral” worldview allowed in the public square because, according to its adherents, it’s the only one that truly advances the social good.

That’s why in the modern era Black Lives Matter slogans and Pride flags are hung in public school classrooms but not the Ten Commandments; why prayer is discouraged from the public square but Drag Queen Story Hour is celebrated; why judges jail pro-lifers for peacefully praying at abortion clinics but refuse to jail or even prosecute pro-abortion activists who violently attack pro-lifers; and why Christian bakers who won’t participate in same-sex weddings are sued for breaking anti-discrimination laws, while football coaches who pray to themselves are fired for publicly “establishing” a state religion.

The Christian culture the Founding Fathers built was eroded and replaced by the slow creep of a new secular religion — and this creep would not have been possible without Everson.

Fighting Back

While Everson and the cases that followed have done tremendous damage, there have been attempts to fight back and reclaim religious liberty in the United States. One need only think back to recent victories at the Supreme Court in Kennedy v. Bremerton, Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, and 303 Creative v. Elenis.

Groups like Alliance Defending Freedom and Liberty Counsel work every day to protect the First Amendment rights of Christians in America. Despite this, it is clear that true religious liberty in America will never be fully recovered unless Everson is overturned by the Court.

In an article for the “Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy,” scholars Timon Cline, Josh Hammer, and Yoram Hazony argue this point, writing that “the Court’s doctrine in Everson stands as perhaps the principal obstacle to the restoration of a sound understanding of the First Amendment [and] to a revived American federalism.”

In other words, the erroneous nature of Everson’s view of the First Amendment will continue to be a major roadblock for Christians in the United States — and as long as Everson lives on, the threats to true religious liberty will remain.

If you like this article and other content that helps you apply a biblical worldview to today’s politics and culture, consider making a donation here.